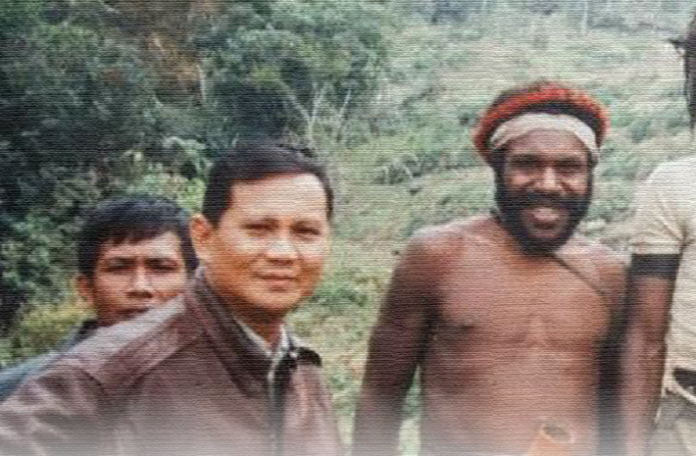

Warrant Officer Bayani is a native Papuan. He is well known in KOPASSUS. He is calm, bold, has incredible shooting and tracking abilities.

During the 1996 Mapenduma hostage rescue operation, we were faced with conflicting intelligence. My instincts told me that it was better to ask an experienced person who had mastered the area. So I summoned Bayani. I asked for his opinions on the information provided by the British intelligence experts. Bayani disregarded it.

He continued to reject the British intelligence even after I told him that the intelligence came from the use of advanced technology to determine the exact location of the hostages. Bayani then gave an explanation that I will never forget.

With a typical Papuan accent, he said, ‘Bapak, not even monkeys would want to be there [pointing to the location tipped by British intelligence], let alone Kelly Kwalik [the kidnapper]. There is no water there. Bapak, how could so many people be there without water.’

Warrant Officer Bayani is a native Papuan. I knew him first as a sergeant. He was recommended to me by my senior at that time, Major Zacky Anwar, who knew Bayani from operations in West Irian at that time. According to Pak Zacky Anwar, Bayani was a great soldier in the field. He had great fieldcraft techniques, great physical strength. He could move in the jungle silently. He was so brave that he once infiltrated an enemy guerilla camp alone without weapons. He went past the sentries toward the men huddled around a fire. He grabbed their rifles and overpowered them. Bring them back as prisoners. He was that type of soldiers. Someone that is always smiling, joking but cool. If ever there was a Rambo in the TNI, I think that Bayani could qualify for that role.

He is well known in KOPASSUS circles. He is calm, bold, and has amazing shooting and tracking abilities. During operations in Papua, he was usually barefoot and only wore shorts.

He possessed the ability to infiltrate the enemy’s camps. Because the enemy thought that he was one of them, he managed to kill several combatants and seize three to four weapons in a single operation. In total, my seniors would tell me in awe that he had seized more than 100 weapons from the enemy’s hands. This was phenomenal because many companies could not even get one assault rifle in one year of operations.

However, Bayani was well known to get in trouble with authorities during his time in the garrison. He was often involved in fights, and I had to release him from the military police several times. The story about Warrant Officer Bayani that I want to share concerns the 1996 Mapenduma military operation to rescue 26 researchers (including seven foreign nationals) on the ’95 Lorentz Expedition to research biodiversity in the West Irian Forest. They were held hostage by the separatist Free Papua Movement (OPM), near Mapenduma, in the central highlands of Baliem Valley, Papua.

I was tasked by General Feisal Tanjung at that time to take on the OPM. I think that was two weeks after I was made a general in December 1995. Can you imagine the challenge I was faced with? As a freshly minted General, I was already deployed on a hostage rescue mission in the middle of the jungle. At that time, the statistics were not favourable to us. Most of the missions failed or suffered immense casualties. Especially hostage rescue missions in the jungle. Mapenduma was the first successful case study in the world despite attempts in the Philippines and Colombia.

At that time, we were hampered by the lack of equipment. The photography equipment we had was not up to standards. We could only take blurry pictures.

We were also hampered by the fact that we did not have maps of that area. This was an unmapped area of West Irian. Anyway, the full story must be told at full length at another time, in another book, to do it justice. Let us give the main lines of the mission.

To free the hostages, I established a core team of expert trackers consisting of troops from KOPASSUS and the Cenderawasih Territorial Command (KODAM). Most soldiers on the team were native Papuan. We called the ‘all Papuan team’ the Kasuari Team, under the command of Warrant Officer Bayani, who we nicknamed the “Papuan Rambo”. He could smell another human being from 100 meters away and could spot a two-week-old trail. Their task was to get into hard-to-reach areas of the rugged terrain and to track down the hostage-takers and hostages if they managed to escape our initial assault.

I had prepared a contingency plan in case the first attack was unsuccessful. Plan B was to deploy troops to pursue and surround the hostage-takers and retrieve the hostages. The Kasuari Team would serve as the main tracking team. Mapenduma Operation was an extremely difficult operation because the hostage location was deep inside Papua’s dense and treacherous jungle.

It was very difficult to find successful hostage rescue operations in the middle of a jungle in the decades prior. Even statistics of the regular hostage-rescue operations were not encouraging. According to an FBI study, out of all hostage-rescue operations, 50 per cent failed, resulting in the hostages and many of the rescue team members being killed.

In 1996, the TNI did not have the luxury of satellites, drones, and reconnaissance aircraft, so it was very difficult to obtain real-time intelligence data. We did not even have a topographic map with a scale of 1:50,000. There was only one hand-drawn map, the copies of which were what the troops used.

We did use GPS. It was probably one of the very first GPS in Indonesia. However, it was not a military-grade GPS but one for civilian use. Nonetheless, it was very useful. Due to the difficult hilly terrain with deep valleys, we equipped the troops with satellite phones because FM radio and SSB radio were unreliable in Papua.

As the time to decide on target location drew near, I asked the intelligence team where exactly the GPK commander Kelly Kwalik and the hostages were.

I wanted to emphasise here that as we had no advanced equipment to determine the target location, human intelligence became crucial. I happened to have an amazing intelligence team, although I only realised about it after the operation had been concluded.

The late Colonel Amirul Isnaini was tasked with leading the intelligence team. His last rank was Major General, and he was also a former KOPASSUS commander.

However, the key officer at the time was Infantry Major Restu Widiyantoro. He was a 1987 graduate and had resigned from the TNI. Major Restu was indeed one of the officers with one of the highest IQs in KOPASSUS, perhaps even in the whole of TNI. I know this because I often made my officers take IQ tests. I made the right decision when I put him on the intelligence analysis team.

The team could not pinpoint a single location. However, their instinct convinced them that the hostage-takers and hostages would be in one of six coordinates in 2-3 days.

Since we had no exact location, I had no choice but to designate those six points as the target area. The airborne raids would be carried out using six assault helicopters deployed to each target.

I had predicted that the element of surprise might momentarily lose its advantage and leave about a 30-minute gap for the hostage-takers to escape with the hostages. Thus, I formed the Kasuari Team as my Plan B. By then, I was ready to deploy them to intercept the hostage-takers should they attempt to flee the target points.

Just before the operation commenced, a team of international advisers from the British SAS (Special Air Services) gave me a piece of crucial information. They told me that they managed to smuggle in a beacon when they sent medicines, food, and clothing to the hostages through the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

According to them, the signal emitted by the beacon could give out the exact location of the hostages. They then used the helicopters I lent them to surveil the area they believed the beacon signal was coming from.

Shortly after, they returned and gave me the exact coordinates. After we checked the coordinates, it was on a high mountain visible from my command post. However, it was outside the six target areas provided by my intelligence team.

Faced with two conflicting intel, one from my team and the other from the SAS, my instincts told me that it was better to ask an experienced person who knows the area well. So, I summoned Bayani. I asked for his opinion concerning the information provided by the British intelligence experts.

Bayani categorically rejected it.

He insisted even though we told him that the intel was gathered using advanced technology. Bayani then gave me the rationale I will never forget.

With a typical Papuan accent, he said, ‘Bapak, forget Kelly Kwalik, not even monkeys would not want to live in that place! There is no water source there. Bapak, how could so many people survive without water up there.’

This was local wisdom from a native, who knew the area like the back of his hand. He knew better about the local terrain than foreigners from afar, despite using sophisticated electronic tracking devices.

I was faced with two dilemmatic options: should I believe in the work of European technology, NATO technology, or believe in the local wisdom of a local sergeant. In a situation like this, I would often rely on my instincts. I chose to believe in my men. After careful deliberation, I conveyed my decision to the British experts.

I decided to perform a heliborne assault on the six locations pinpointed by my intelligence team. One of the six locations turned out to be accurate. We managed to rescue the hostages despite suffering some casualties. Out of the 26 hostages, three of them were killed by the hostage-takers. The rest were rescued, including all the foreigners.

The successful outcome of the Mapenduma hostage crisis earned praise from the international world, raising the profile of the TNI, the reputation of the Indonesian government, and the prestige of the nation as a whole. We had been negotiating for months and made concession after concession. However, when the hostage-takers violated the consensus, the TNI did not hesitate to take the action needed.

I am very proud of this achievement. However, I now also realise that the operation many dubbed “Mission Impossible” owed its success partly to Warrant Officer Bayani’s courage, insight and assertiveness. With confidence, he managed to convince a general, a high-ranking Indonesian officer. He had played a key role, sparing Indonesia from humiliation.

I was also very proud that my instincts were correct to follow my men and not be intimidated into over-relying on sophisticated Western technology. One British officer even remarked: “Only James Bond can pull this off. Only James Bond can succeed in this type of operation.” After we succeeded, perhaps these foreigners would now consider us the equal of James Bond. The only difference was, James Bond is fiction. Our soldiers were real, and we succeeded in reality, not in a film.

Those are some of the characters and events that have influenced my life as a soldier. They have shaped my leadership style. They have granted me insights on military leadership and the importance of excellent armed forces to maintain the nation’s independence, sovereignty, and security.

As a nation, we should be peace-loving and conflict-averse. However, without superior armed forces, other countries stronger than us may annex our territory, steal our wealth, divide us, and eventually make us suffer. The history of human civilisation, full of bloody conquests, has taught us this. Our archipelago has been the receiver of so many foreign invasions and interventions throughout several hundred years.

I always remember the teachings of the great Greek historian Thucydides: ‘The strong will do what they can, and the weak will suffer what they must.’